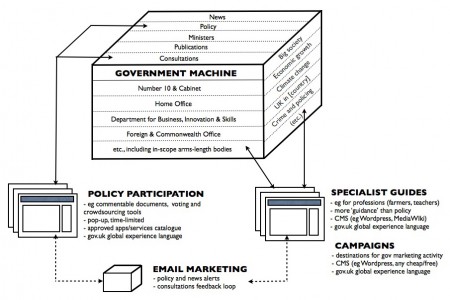

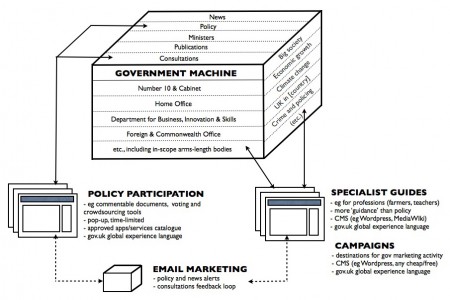

In which Simon makes the case for the ‘government machine’ (in the diagram above), for government departments to publish fairly basic written information about their work, to be built on something which already exists, instead of being built ‘from the ground up’. If you haven’t already, do read Neil’s piece… then Stephen Hale’s piece about the Department of Health’s new approach… then read on. And do please note the line about ‘Seriously, this isn’t about WordPress.’

It won’t entirely surprise you to learn that, when Neil Williams’s blog post about government web publishing in the world of a Single Domain popped up in my feeds, the first thing I did was press control-F, and search for ‘wordpress’. And hooray, multiple mentions! Well, yes, but.

Some background, for those who need it: Neil is head of digital comms at BIS, currently ‘on loan’ to the Government Digital Service team, to lead the work exploring how government departments fit into the grand Lane Fox / Loosemore / Alphagov vision. A ‘hidden gem‘, Tom Loosemore calls him – which seems a bit harsh, as Neil has been quite the trailblazer in his work at BIS, not least with his own web consolidation project. It’s hard to think of anyone better placed to take up this role.

With that track record, it’s happily predictable to see Neil reserving a specific place for WordPress (and the like). More generally, the vision – as illustrated in the diagram reproduced above – is sound, with the right things in the right places. There’s so much to welcome in it. But there’s one line, describing an ‘irreducible core‘, which stopped me in my tracks:

a bespoke box of tricks we’ll be building from the ground up to meet the publishing needs most government organisations have in common, and the information needs ‘specialist’ audiences most commonly have of government.

Here’s my question for the GDS team: why bespoke? why ‘from the ground up’?

It’s a decision which requires justification. ‘Bespoke’ invariably costs more and takes longer. It will increase the risks, and reduce the potential rewards. It would also seem to be directly in breach of the commitment Francis Maude made in June 2010, to build departmental websites ‘wherever possible using open source software’. Were all the various open source publishing platforms given due consideration? Was it found to be literally impossible to use any of them, even as a basis for development?

Let’s assume WordPress and Drupal, the two most obvious open source candidates, were properly considered, as required by the Minister. Let’s assume contributions were sought from people familiar with the products in question, and just as importantly, the well-established communities around them. Both are perfectly capable of delivering the multi-view, multi-post type, common taxonomy-based output described in the ‘multistorey’ diagram. Both are widely used and widely understood. So why might they have been rejected?

Did the team spot security or performance issues? If so, wouldn’t the more responsible, more open-source-minded approach be to fix those issues? Then we’d all see direct benefits – on our own personal or company websites – from the expert insight of those hired by our government. If things are wrong with such widely-used technologies, whether inside or outside government, it’s already government’s problem.

Or were there particular functions which weren’t available ‘out of the box’? If so, is it conceivable that someone else might have needed the same functions? Local government, perhaps – for which the GDS team has ‘no plans or remit‘. We’re seeing plenty of take-up of WordPress and Drupal in local government land too. They have very similar needs and obligations as regards news and policy publication, consultations, documents, data, petitions, biographies of elected representatives, cross-cutting themes, and so on. Why not make it easy, and cheap, for them to share in the fruits of your labours?

But I think it goes wider than different tiers of government. Government is under a moral obligation to think about how its spending of our taxes could benefit not just itself, but all of us too.

Even if this project’s bespoke code is eventually open-sourced, the level of knowledge required to unpick the useful bits will be well beyond most potential users. Given that it’ll probably be in Ruby or Python, whose combined market share is below 1%, it won’t be much use ‘out of the box’ to most websites. A plugin uploaded to the WordPress repository, or a module added to Drupal’s library, would be instantly available to millions, and infinitely easier to find, install and maintain. (Well, certainly in the former case anyway.)

I can’t help thinking of the example of the BBC’s custom Glow javascript library, which does simplified DOM manipulation (a bit like jQuery), event handling (a bit like jQuery), animations (a bit like jQuery), etc, proudly open-sourced two years ago. It appears to have attracted a grand total of 3 non-BBC contributors. Its second version, incompatible with the first, remains stuck at the beta-1 release of June 2010. Its Twitter account died about the same time; and its mailing list isn’t exactly high-traffic. I’m not convinced it ever ‘unlock[ed] extraordinary value out there in the network‘. Proof, surely, that open-sourcing your own stuff isn’t the same as pitching in with everyone else.

Seriously, this isn’t about WordPress – although that’s unquestionably where the Whitehall web teams’ desire path leads. It’s not really even about open source software. It’s about government’s obligation to the citizens and businesses which fund it. It’s about engaging with existing communities, instead of trying to create your own. Acknowledging people’s right to access and make use of the data – erm, sorry, the code – whose creation they funded. Any of that sound familiar?

There’s so much right about the picture Neil paints. And maybe I’m reading too much into a single line. But the idea of building yet another bespoke CMS to meet Whitehall’s supposedly-unique requirements seems to be three to five years out of date. And it didn’t work too well, three to five years ago. Or three to five years before that. Or…