Puffbox emerges briefly from retirement to bring you an extract from Computer Weekly’s write-up of a somewhat confrontational appearance by Work and Pensions Secretary Iain Duncan Smith and DWP officials before the Commons Work And Pensions Committee, and a reported £40m write-off of IT work.

Universal Credit director general Howard Shiplee also revealed that the new system being developed will use open source, and he implied it will use cloud-based services.

“The digital approach is very different. It depends not on large amounts of tin. We will use open source and use mechanisms to store and access data in [an online] environment. It is much cheaper to operate and to build. We don’t have to pay such large licence fees,” he said.

When asked why that approach was not taken in the original plans for Universal Credit – where an agile development approach was adopted, then switched to waterfall when agile failed, Shiplee said, “Technology is moving ahead very rapidly. Such things were not available two-and-a-half years ago.”

Funny, that. Because…

- The Cluetrain Manifesto was published in 2000, followed in 2001 by the Agile Manifesto for software development.

- In 2004, the Office of Government Commerce said open source was ‘a viable and credible alternative to proprietary software’.

- In October 2008, Amazon EC2 came out of beta after two years of successful operation.

- In 2009 there was a UK government policy statement which, I felt, explicitly tipped the scales in favour of open source.

- In early 2010 that policy was further beefed up, requiring suppliers to show they had given ‘fair consideration of open source solutions’ – and if they hadn’t, they faced being ‘automatically delisted from the procurement’.

- In July 2010, following the general election, the Cabinet Office specifically acknowledged that ‘open source software offers government the opportunity of lower procurement prices, increased interoperability and easier integration’.

- In March 2011, over two and half years ago, HMRC claimed to have ‘transformed [its] website, which as you know is one of the largest websites in the UK if not in Europe, to actually become a completely open source technology.’

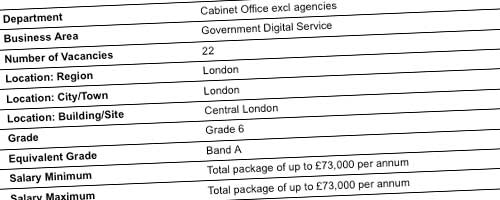

Mr Shiplee is the director general of a project designated as one of the government’s 25 exemplars of digital transformation. His background, though, is in development of a more concrete kind: he was director of construction for the London Olympics. It’s unfair to expect him to be an expert in government technology policy. But one is left wondering how he was briefed.

No matter what you may have been encouraged to believe, there was life before the creation of the Government Digital Service.