If there’s one commitment in the Conservatives’ Technology Manifesto, billed as ‘the most ambitious technology agenda ever proposed by a British political party’, which makes my heart leap with joy, it’s this:

We will also create a small IT development team in government – a ‘government skunkworks’ – that can develop low cost IT applications in-house and advise on the procurement of large projects.

For those unfamiliar with the term, ‘skunkworks’ was devised by aircraft maker Lockheed Martin – and is still jealously guarded by them as a trademark. It describes a small, almost secret unit within a large organisation, protected from all the internal bureaucracy, and given carte blanche to be creative. Among Lockheed Martin’s 14 rules for its operation are:

- Unit manager to be answerable directly to a very senior member of the organisation.

- An ‘almost vicious’ restriction of the numbers of people involved.

- Minimal reporting requirements.

- Strict access controls.

- Mutual trust, with close cooperation and daily liaison, allowing correspondence to be kept to a minimum.

All very ‘web 2.0’… until you learn these rules came together in the 1940s.

I detect the influence of Tom Steinberg. Eighteen months ago, at MySociety’s 5th birthday celebration, Tom gave a speech in which he said:

So long as the cult of outsourcing everything computer related continues to dominate in Whitehall, and so long as experts like Matthew [Somerville] and Francis [Irving] are treated as suspicious just because they understand computers, little is going to change.

Government in the UK once led the world in its own information systems, breaking Enigma, documenting an empire’s worth of trade. And then it fired everyone who could do those things, or employed them only via horribly expensive consultancies. It is time to start bringing them back into the corridors of power.

But equally, as I argued at the time, bringing those kinds of people back into Whitehall and then dumping them inside IT departments wasn’t going to help either. This skunkworks concept – where you’re effectively a startup within the organisation – should offer the best of both worlds.

I’ve been one of numerous people – inside and outside government – who have suggested such an approach in the past. And no matter how positive a hearing the idea received, it didn’t happen. Its time may well be coming.

My suggestion is that this unit needs to be created very, very quickly after the election. I remember the uncertainty and sheer chaos which followed the handover from Tories to Labour in 1997. Radical, dramatic, shocking, good things happened. For a while, you went into work each day not knowing what was coming next. It was magnificent, wonderful chaos – for a while.

There’s also a specific paragraph on government websites:

The Conservative Party believes that government websites should not be treated like secure government offices or laboratories, where public access is to be controlled as tightly as possible.

We see government websites as being more like a mixture of private building and public spaces, such as squares and parks: places where people can come together to discuss issues and solve problems.

Where large amounts of people with similar concerns come together, for example filling in VAT forms or registering children for schools, we will take the opportunity to let people interact and support each other.

Again… Mr Steinberg, I presume? I’m not sure quite what that’s getting at; discussion forums? opening up Sidewiki-esque comments on ‘standard’ pages? (That idea was first aired at the 2008 Barcamp.)

There’s a commitment to ‘a level playing ?eld for open source IT’: welcome words, but we already have an on-paper commitment to a level playing field… or arguably, ever-so-slightly slanted in favour of open source. I haven’t changed my mind since January this year, when I concluded that we need a ‘specific high-profile victory for Open Source, to give it real momentum in government’. And those mythical 100 Days could be the time to deliver that.

Elsewhere there’s confirmation of notions already floated: transparency of senior salaries and contract spending, a ‘right to data’, online publication of expenses claims at Parliament and council levels, and so on.

In some aspects, there’s little to separate the rhetoric between Labour and the Tories. But whereas Labour has had the opportunity to make ambitious changes happen – and hasn’t always taken them, you get the sense of energy and ambition in the Tories’ promises.

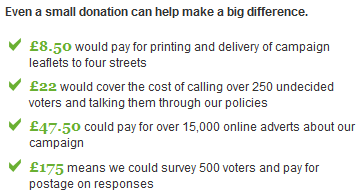

There are specific actions and measurable commitments in this document: and it must be said, there’s evidence of the Tories practising what they’re preaching – use of WordPress and Drupal, publication of government IT policy (admittedly, someone else’s) in commentable form, publication of front-bench expenses via Google Spreadsheet.

Things could be about to get very, very interesting.