The Government Digital Service’s Implementer Guide for the new cookie rules recommended that site owners should audit their sites, and look to reduce ‘unnecessary and redundant cookies’. With or without the new rules, it’s still sound advice. So I thought I’d share a couple of things we’ve done for clients, which might be helpful to other people.

It’s easy enough to look at the cookies being dropped by your own site, but life becomes a lot more difficult when it comes to third party services. You might not realise it, but every time you embed a YouTube video on a page, you’re exposing your users to YouTube cookies. And if you’ve included Twitter’s excellent profile widget on your site, guess what? – it’s dropping cookies too.

Both services would probably argue that any user tracking is ultimately for users’ benefit: and in fact, unlike many in the web industry, I have some sympathy for that argument. But I’m not entirely comfortable with government websites acting as (unwitting?) conduits between users’ personal web histories and third-party services.

YouTube

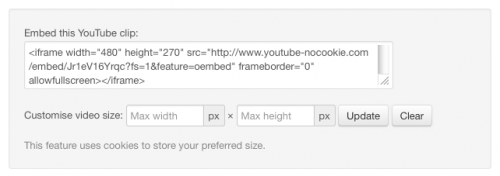

YouTube offers a seamless solution: a parallel domain, youtube-nocookie.com which gives you the exact same YouTube playback function, but tighter controls over cookies. If you’re ever embedding a clip manually from youtube.com, you’ll see an option to ‘Enable privacy-enhanced mode’: tick this, and you’ll see the embed code’s reference to youtube.com change to youtube-nocookie.com. Easy as that.

(The name is slightly deceptive: it doesn’t completely eliminate the use of cookies. YouTube’s help pages indicate: ‘YouTube may still set cookies on the user’s computer once the visitor clicks on the YouTube video player, but YouTube will not store personally-identifiable cookie information for playbacks of embedded videos using the privacy-enhanced mode.’)

On a couple of client sites with large quantities of videos, FreeSpeechDebate and the Government Olympic Communication site, we use a WordPress custom post type to simplify the process of adding YouTube content. All they need to do is paste the URL of the clip’s page into a WP editing screen, and we extrapolate all the rest: embed code, thumbnail image, dimensions and so on. The videos are then included automatically at the top of the appropriate page.

We’ve now altered that functionality to serve all videos from the youtube-nocookie.com domain; and also to include the youtube-nocookie.com domain in the embed code we offer. A fairly simple case of find-and-replace, initially in the page template’s PHP, and subsequently also in javascript if users want to customise the dimensions.

Avoiding Twitter’s cookies has been slightly trickier. Our solution has been to move clients away from the official Twitter widget, instead deploying my colleague Simon Wheatley’s well-established Twitter Tracker plugin (downloaded well over 10,000 times), which we’ve adapted to permit cookie-free usage.

Twitter Tracker adds two new WordPress widgets: one showing Twitter search results for your chosen term or hashtag, the other displaying all tweets by a given user. It includes local caching of the data, minimising traffic to Twitter and (in all likelihood) rendering the pages much faster – for the loss, admittedly, of a ‘real time’ view, which may or may not be important to you.

However, because the widgets call users’ profile images live from twitter.com, cookies were still being dropped. So there’s now a ‘partner plugin’, called Twitter Tracker Avatar Cache, which – as the name suggests – downloads any Twitter profile images and saves them locally within WordPress. No need to call them in from twitter.com, and hence no cookies. (For those who don’t want this extra functionality, the base plugin will continue to work as it always has.) It’s available now from the WordPress plugin repository: find it via the ‘Add New’ screen in your WordPress admin interface.

For most people, this will probably seem like overkill – and in fairness, it probably is. But for quite a few of our clients, it’s been a helpful way to avoid some of the more sensitive issues around cookies and usage tracking, without compromising on site functionality.