I must admit, I was a bit surprised to receive an invite to what was billed as the launch of the Government Digital Service – but was, more accurately, the housewarming party for its new offices at Holborn. I consider myself a ‘critical friend’ of the project, but it’s clear that some people focus on the ‘critical’ part. I had visions of one of those American police sting operations, where they tell all the local fugitives they’ve won the Lottery.

Looking back at the tweets afterwards – from people who were there, and those watching from afar – I was surprised at quite how big a deal people were making of it. I observe these matters more closely than most, I admit; but I didn’t hear a lot I hadn’t already heard before. Some of it several years ago.

What was more important, by far, was who said it. And where.

Leading off the sequence of rapid-fire speeches and presentations (slides now on the GDS blog) was Cabinet minister Francis Maude: note the open-neck shirt, the relaxed saloon-bar lean against the side of the podium. This was not your typical Address By The Minister. Citing his pride that this was happening on his watch, Maude made a somewhat unexpected statement: ‘where a service can be delivered digitally, it should be, and only digitally.’ That sounded like a step beyond the notion of ‘digital by default’. Had I taken that down correctly? Yes I had; helpfully he said it again. And again. Fair enough…

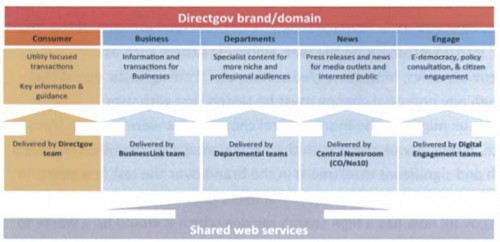

The honour of following the Minister fell, perhaps unexpectedly, to Ryan Battles from Directgov. In fact, this was a recurring theme throughout the morning: it felt like every opportunity was taken to credit Directgov, how much it had achieved, how strong its satisfaction ratings had been.

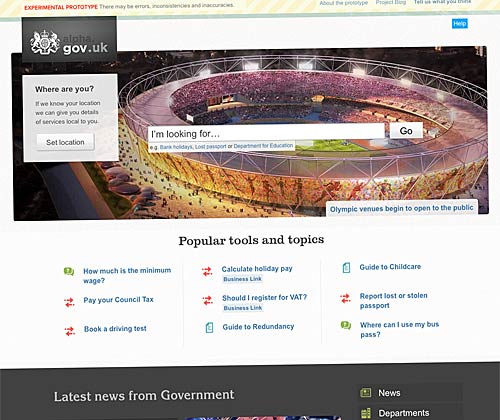

Tom Loosemore’s slot was probably the most eagerly anticipated: a first public sight of screens from the Single Domain ‘beta’ build. He opened with a tribute to Directgov, and said he now appreciated how difficult it was to get things done in government. And via an extended jigsaw metaphor, he demonstrated some of the new site’s key principles – most notably the use of ‘smart answers’ javascript-based forms which asked specific questions, and gave specific answers. (I’ve got a story of my own to tell about such approaches… another time.)

But for me, Chris Chant’s comments may prove the most significant of all. He described how the GDS’s IT had been set up, using the kind of instant-access, low-cost tools you’d expect of a technology startup. Mac laptops, Google Apps, the open-source Libre Office software suite, and no fixed telephony. (OK, so maybe the Mac laptops wouldn’t be low-cost to buy initially; but they’re more developer-friendly, and almost certainly lower-cost to support.)

I think that’s when it all fell into place for me. The day wasn’t about demo’ing the current work-in-progress on the websites. It was about presenting GDS itself as a vision of the future. It’s an office space which looks and feels like no government office I’ve ever been in: and for many, it’ll come as quite a shock to the system. (Not least the ceiling-height photos of Francis and Martha.)

It’s taking a pragmatic, rather than the usual paranoid and overbearing view of IT security; and a modern approach to ‘desktop’ computing. Which of course is the only sensible thing to be doing in this day and age… although that hasn’t been enough to encourage government to do so in the past.

Ian Watmore’s comments confirmed this: one of the first things Mike Bracken had asked for upon his appointment was ‘a building’ – and this was it. Perhaps appropriately, Watmore observed, it’s a former church. As might be expected of a Permanent Secretary, his remarks seemed the best-prepared – although, as he freely admitted, the previous night’s football results must have been quite a distraction for an avid Arsenal fan.

Some visionary remarks from Martha Lane Fox, about technology providing a route out of poverty, brought the procession of Big Names to a close. It’s hard to imagine a more illustrious lineup of speakers for such an event; (almost) all of them speaking without notes, and with conviction. These were the people at the highest levels of the department in overall charge of public services, all speaking as converts to the benefits – to the user, to the civil servant, to the taxpayer – of the new tech-led approach. There’s absolutely no questioning the backing for it.

And by their very mode of operation, GDS is setting precedent after precedent, about what is allowed, and can be done in a Civil Service environment. Others can point to it as an example, and ask difficult questions of their own IT and facilities managers. If they can do it, and apparently save something like 82% by doing so – why can’t we? Or more to the point, how the hell can we justify not doing so?

Things are changing.

Although I don’t believe there’s been any kind of formal announcement yet, I’ve had it confirmed from various well-placed sources that Chris Chant, the Cabinet Office’s programme director for cloud computing (salary £125-129.9k), has been named as ‘interim’ CEO for Digital – the all-powerful position recommended by Martha Lane Fox in her

Although I don’t believe there’s been any kind of formal announcement yet, I’ve had it confirmed from various well-placed sources that Chris Chant, the Cabinet Office’s programme director for cloud computing (salary £125-129.9k), has been named as ‘interim’ CEO for Digital – the all-powerful position recommended by Martha Lane Fox in her